DAITERLENS

Film photographer, camera engineer, human renderer.

HOW LIGHT SHINES THROUGH THE CAUCASUS PART 1: CITIES AND CULTURE

Category: Photography

Subcategory: Political / Travel / Portrait

Country: Azerbaijan

Gear used:

Camera: Voigtlander Bessa R2A

Lenses: Voigtlander 50mm f/1.2 Nokton VM + Voigtlander 28mm f/2 Ultron Vintage VM

Nighttime film: Cinestill 800T (one roll)

Daytime films: Kodak Portra 400, Cinestill 50D, Karmir Film 160 (one roll, locally made in Yerevan. And they're scaling up!)

Slide film for portraits and a bit of street work: (the legendary) Kodak Ektachrome 100 (one roll)

"Is there a medical doctor onboard?" rang over the intercom of flight LH612, Frankfurt -> Baku. "If so, please come to Aisle 22 immediately."

It was only fitting that there be a medical emergency before I even landed in Baku to start my journey.

My boss's words kept ringing back. "Stay safe. Be vigilant." One tarmac-skid landing (and a heavy sigh of relief) later, and we had arrived in Heydar Aliyev International Airport.

My friend picked me up in the airport: she was the only person I knew in all of Azerbaijan, and (her words) "I wouldn't have it any other way." Azeri hospitality is difficult to over-embellish: it's impossible to exaggerate something that seemingly has no bounds. After hearing that I was going to attempt to martshuka (mini-bus) through the countryside of Azerbaijan to remote Russia-bordering villages like Quba, she immediately forfeited her limited time home to be a volunteer host for a combined three weeks. "There's no way you'll navigate the system alone," she messaged a week before I boarded my plane. "I'm coming with you.”

It was only fitting that there be a medical emergency before I even landed in Baku to start my journey.

My boss's words kept ringing back. "Stay safe. Be vigilant." One tarmac-skid landing (and a heavy sigh of relief) later, and we had arrived in Heydar Aliyev International Airport.

My friend picked me up in the airport: she was the only person I knew in all of Azerbaijan, and (her words) "I wouldn't have it any other way." Azeri hospitality is difficult to over-embellish: it's impossible to exaggerate something that seemingly has no bounds. After hearing that I was going to attempt to martshuka (mini-bus) through the countryside of Azerbaijan to remote Russia-bordering villages like Quba, she immediately forfeited her limited time home to be a volunteer host for a combined three weeks. "There's no way you'll navigate the system alone," she messaged a week before I boarded my plane. "I'm coming with you.”

Riding into Baku usurped any ideas I had about what an oil state's capital city would be. Posh Parisian apartments surround a central. sandstone-laden old city. To the west, freshly minted skyscrapers like the Flame Towers dominate the skyline from every angle. And along the coastline, ice cream and coffee stands dot the boardwalk, the city's primary escape from bumper-to-bumper traffic jams. It's a city that packs a sea, a mountain, and a city into a tight 50km^2 central area -- and with style.

And when the sun goes down, the city becomes alive. Throngs of people flood the streets, the younger population usually staying out until the early morning in ultra modern clubs like Enerji or wine bars like Room. Colombian boxers, English aristocracy, Azeri Red Crescent workers - you can find anyone you want crowded around a bar. The social dynamic bleeds through a local filter: gossip spreads, and PDA's strictly off-limits. Overall, it's a fairly peachy atmosphere: people are easy to talk to, but there are boundaries you simply don't cross.

But like one shock after another, going to the north and the west of the country uprooted all of those opinions about Azerbaijan thus far.

Heading into the countryside of Azerbaijan for even half an hour shows the incredible speed with which Baku has sprinted towards modernity, while villages fight to preserve culture and languages that have existed for thousands of years. And it's easy to see how these languages avoided the touch of time: the Caucasus are an incredibly walled-off garden, surrounded by massive ranges of mountains, waterfalls, and snow. During the Caucasus Wars, it took Russia half a century to invade. During WWII, Hitler barely began any attempt at this region before turning back. The nooks and crannies of the mountains can only be accessed by Lada, and even then, it's a rough ride to ascend.

These contrasts ricochet throughout the Caucasus. Lakeside resorts like Gölgöl only separate themselves by tens of kilometers from conflict areas. Hiking to a waterfall could very well mean hiking to a Russian border crossing point. Even Nakhchivan, the birthplace of Azerbaijani nobility, is currently walled off from the rest of the country.

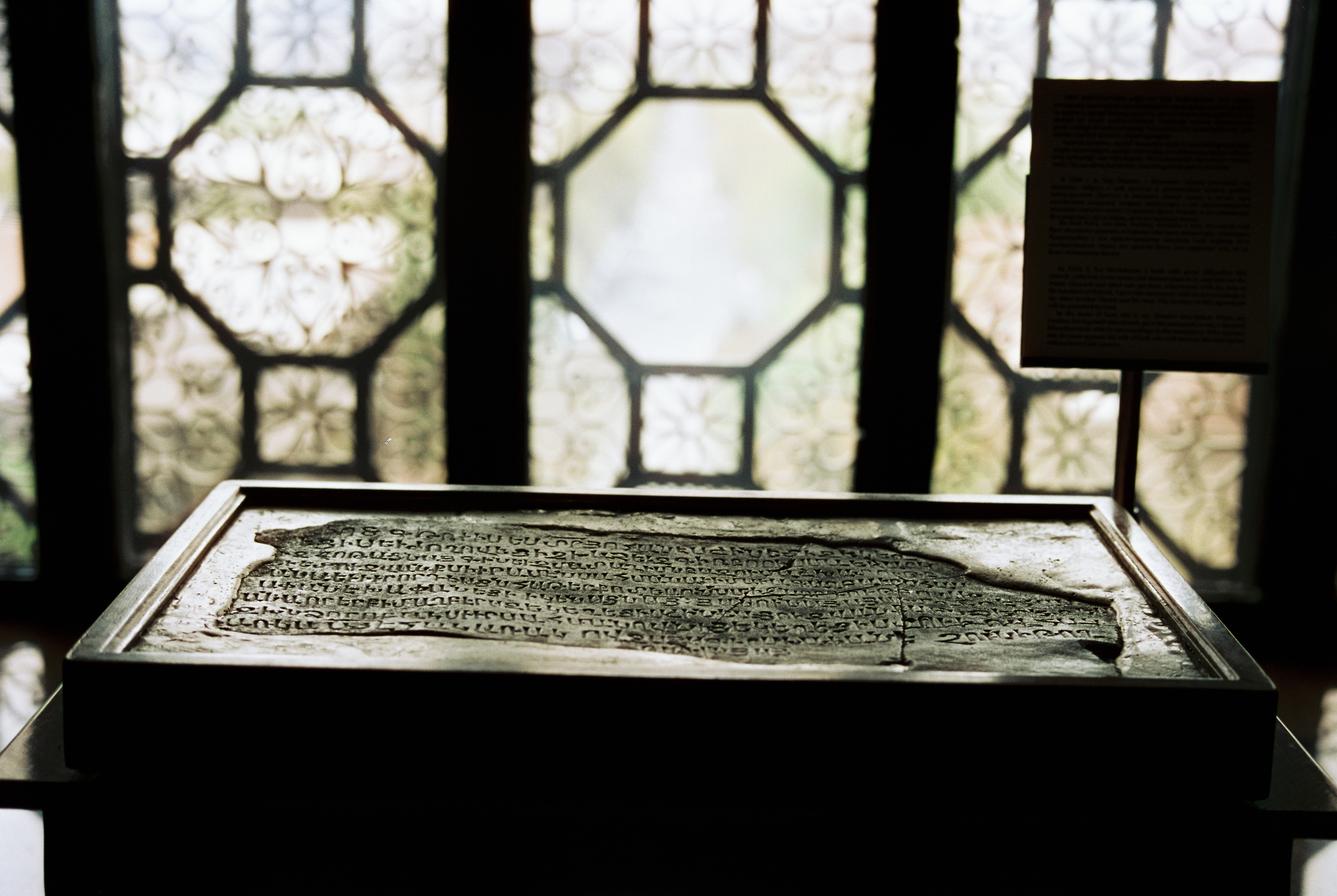

CULTURAL RESILIENCE

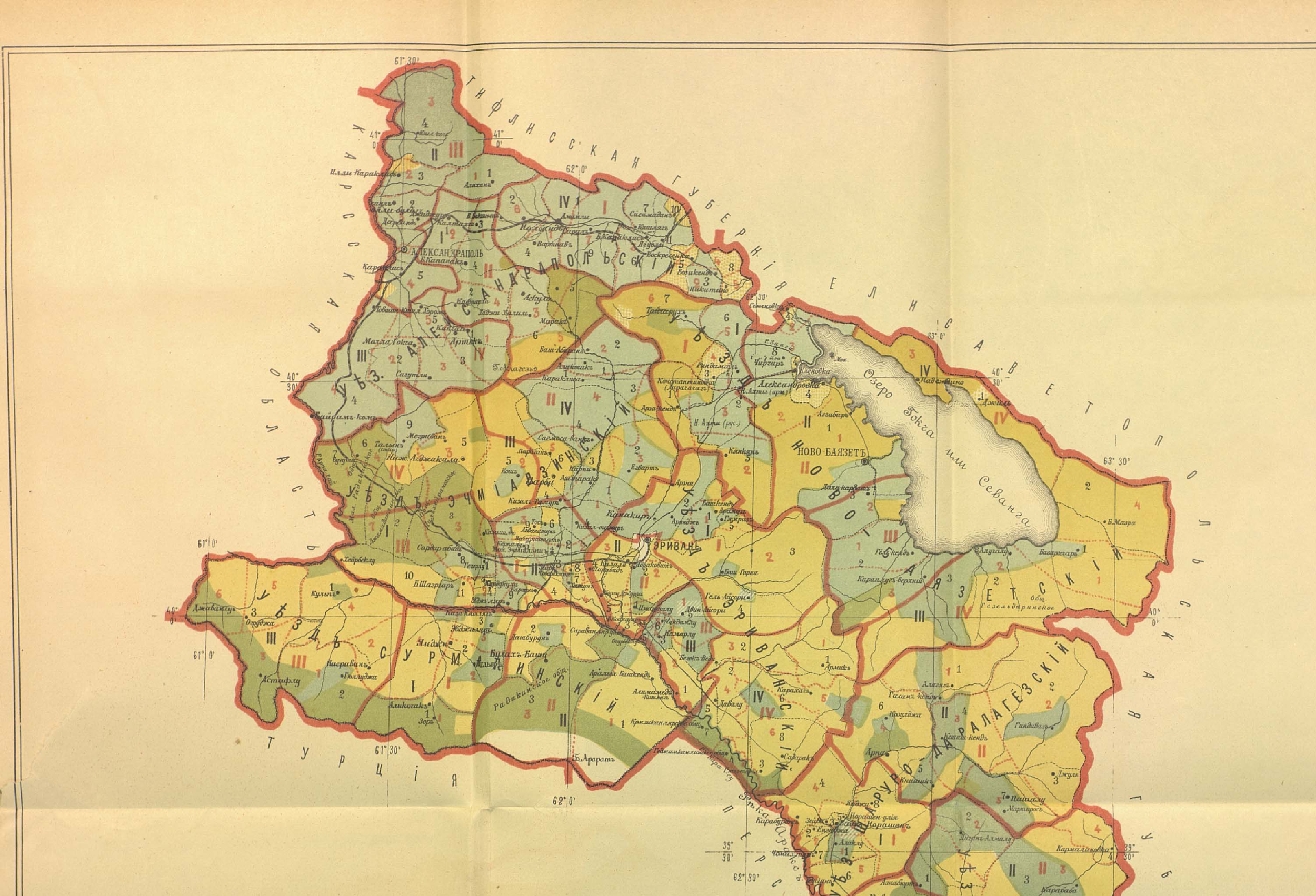

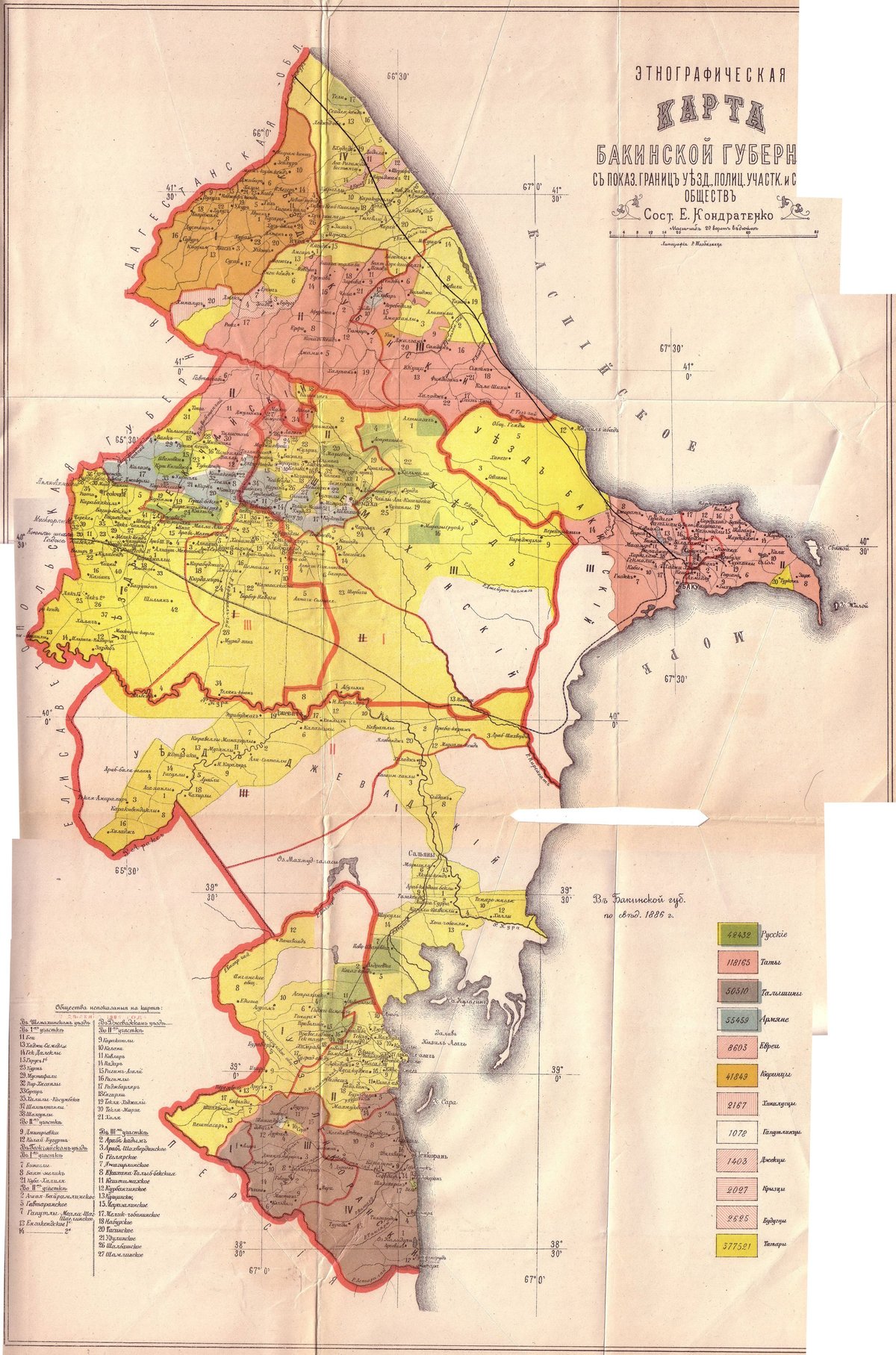

If you look back at ethnographic maps, you'll notice these demographics and cultures haven't changed positions much within even the past 100 years. Here's a side-by-side comparison of the Erivan Governorate and Baku's census data, published in the late 1890s. (Fun side-fact: the Erivan portion was acquired by Russian State Police manually, a method deemed "barely illegal".)

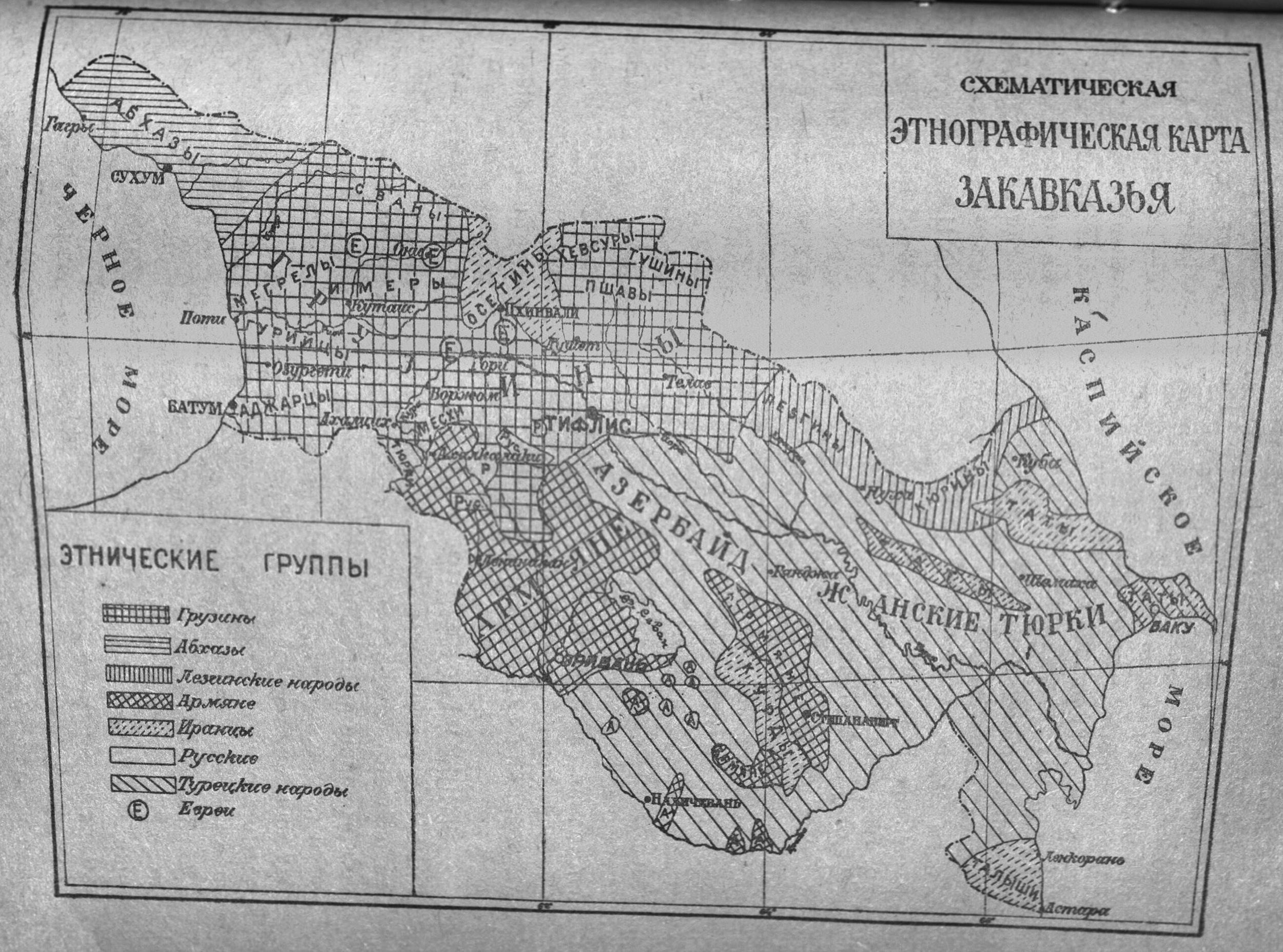

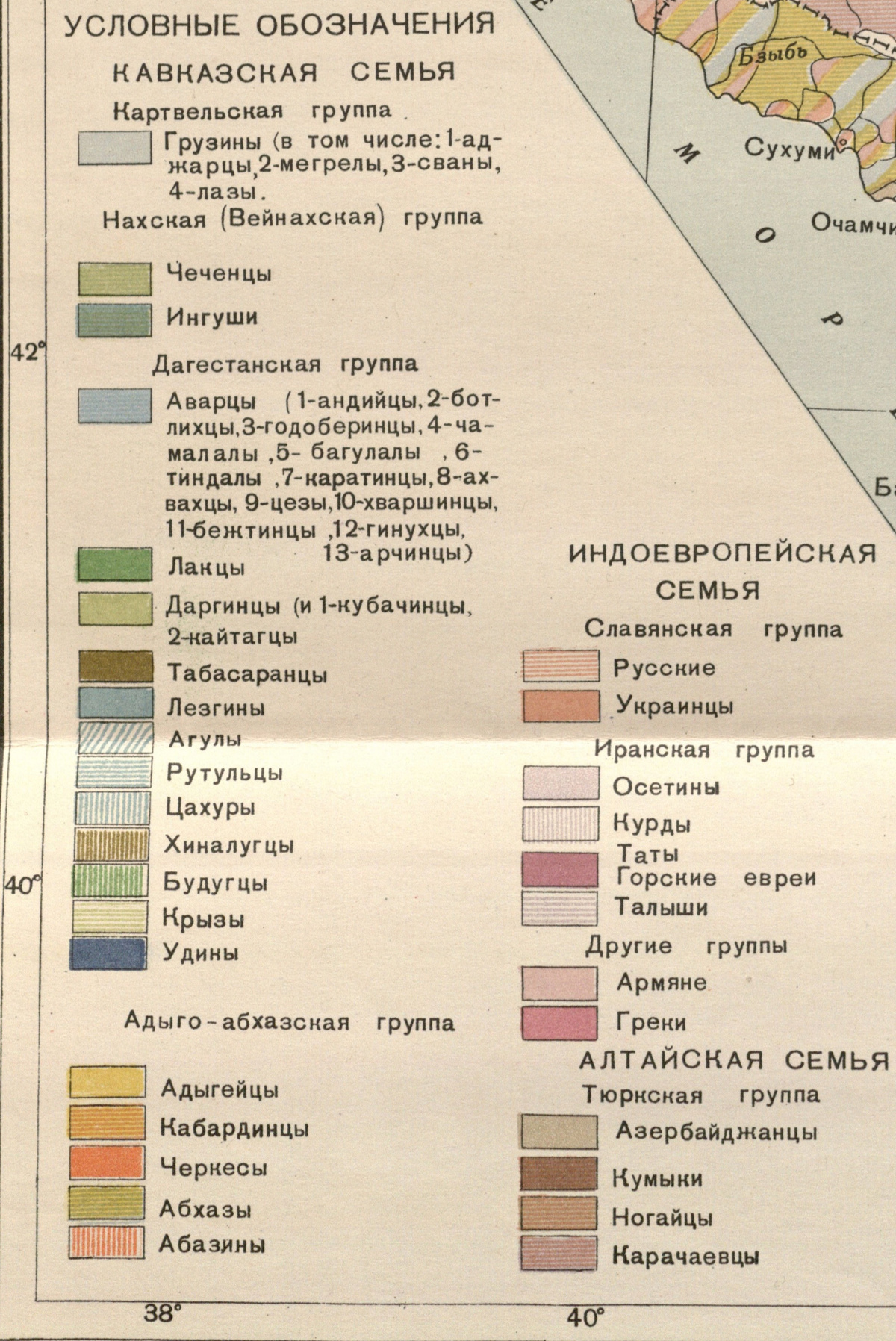

Now check this out: as more maps come through, tracking (mostly) the same groups of people...the pockets don't change. Take the Talysh in the bottom right knob of the Baku map, bordering Iran (depicted in red). It's similar through any ethnographic map you look through, from the late 1890s to present day, even in the face of Soviet assimilation attempts.

And it's not like these are inaccessible communities. The photos below are from the Lezgic villages (upper-right hand side, Baku / Azerbaijan map) we hiked through, near Qriz (a town a few km south of the Azeri / Russian border).

“The only other American we’ve met was recording data for a linguistics PhD”

- A local mountaineer we grabbed tea with, Qriz, Azerbaijan

You can see other forms of cultural resilience throughout ex-USSR states (...Ukraine, 2014 / 2022), without a doubt. But being able to just drive for four hours out of Baku and see this / hear an entirely different language shatters the Western projection of "the Russian monolith" I had grown up with in America.

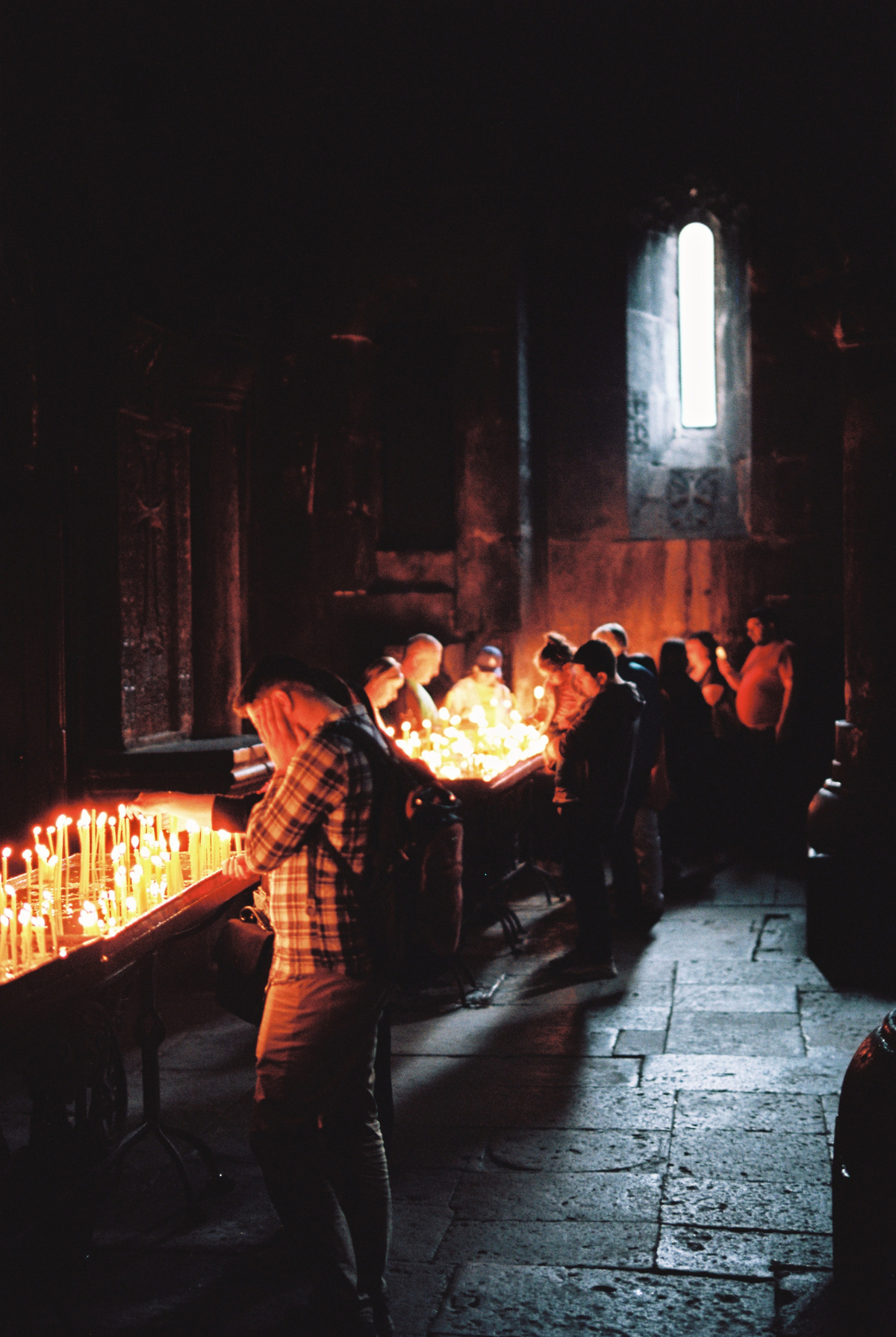

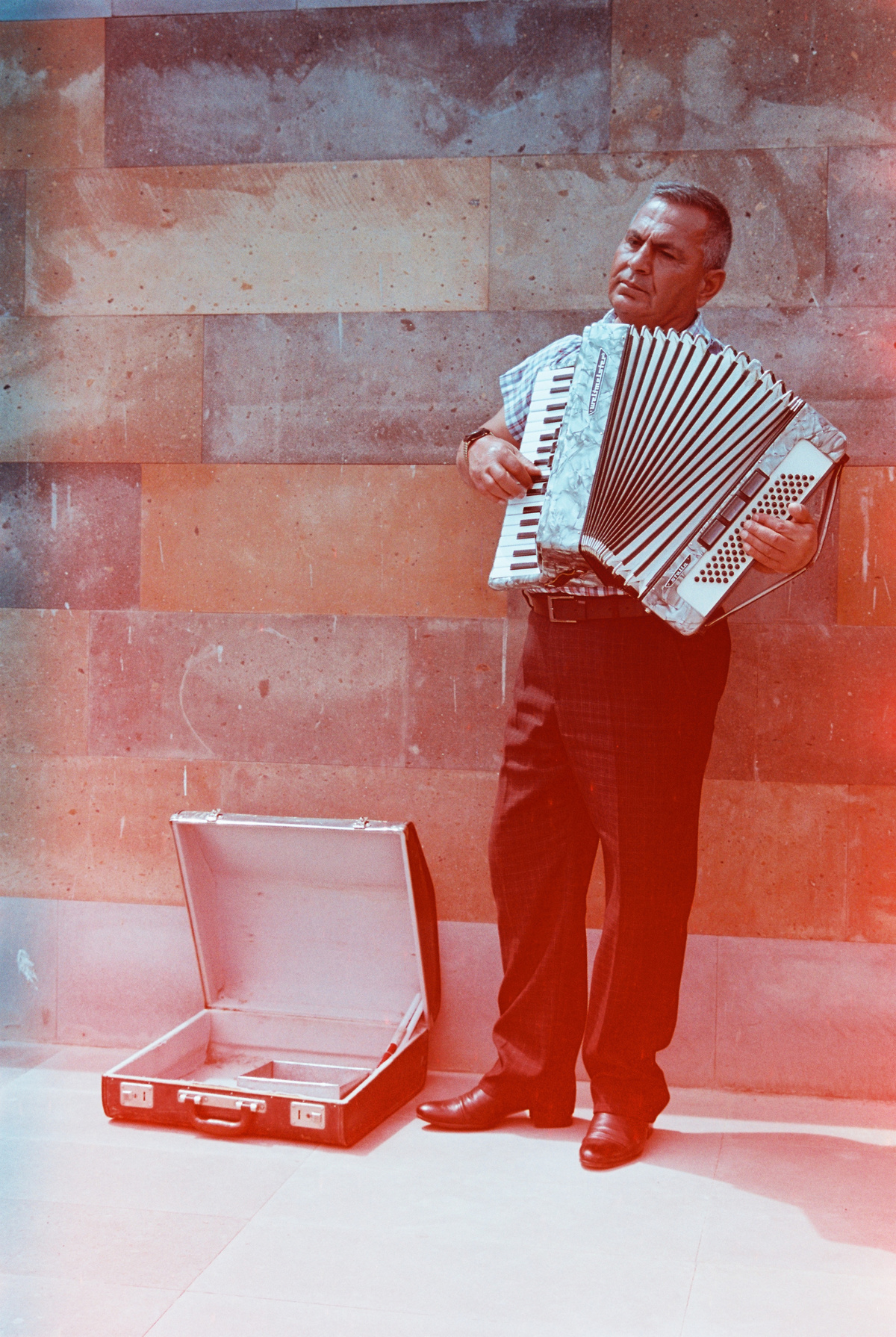

Armenia carries a similar ping-ponging effect as well: modern capital, tucked-away minority cultures. Hipster coffee shops, health food brunch places, and new wave art monuments line Yerevan's streets. A kids' skatepark sits in front of the largest church in town. A new co-working space currently occupies an ex-Soviet post office, co-run by Armenians and Russians, hosting photography shops and hipster clothing stores. One of the most famous photographers in the country, Arthur Lumen, currently owns coffee shops that host local film depositories for local processing. But, cross through the "portal to Kond", and you're back in a suburb founded in the 17th Century untouched by the rest of the city's development construction companies. And with the flood of Russians heading to Yerevan from the 2022 Ukraine war, even more construction is planned for the upcoming future.

Yerevan, Armenia

And as soon as you leave Yerevan, you'll find thousand year old monasteries in Geghard, hiking trails in Dilijan, and your fair share of dubious Turkish-Armenian border crossings in Khor Virab. Again, the contrast that the landscape packs within a 30 minute drive is limitless throughout the Caucasus, with a sprawl of tucked away subcultures.

Even now, as Baku and Yerevan have undergone a deluge of construction and warp-speed renovation into the modern era, villages remain a springboard into tangible history, well-guarded languages and meticulously preserved cultures. It's truly incredible to witness.

And as obligatory when talking about the Caucasus, Ladas.